|

Food For Thought

Russia is the Villain!

Sajai Jose

The hunger and livelihoods crisis that has gripped

the world since Covid-19 hit, exacerbated by the lockdown-related disruptions, has now positively ballooned into an emergency. The crisis is manifesting at just about every level: steadily increasing prices of food, but also of fuel and fertiliser (both directly linked to food prices); growing shortages of food and fuel locally, disruption of global supply chains; increasing unemployment and poverty, and the resultant fall in incomes and purchasing power for the majority; conflict-related disruptions and uncertainty; looming financial crisis and recession; growing public protests directly linked to these; and topping it all, widespread political paralysis, enabled by media silence on the crisis. In sum, people are seeing a multi-pronged crisis unprecedented in its breadth and depth in recent history, and from which few nations seem exempt.

If one is to believe Western leaders and international organisations such as the United Nations, the crisis is primarily a product of Russia’s war in Ukraine. A UN task force report on the issue was titled ‘Global Impact of war in Ukraine: Billions of people face the greatest cost-of-living crisis in a generation.” UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres was quoted as saying that the war was “supercharging” the crisis in poorer countries that were already struggling to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change.

Addressing the G7 summit in Germany this June, US President Joe Biden too blamed the crisis on “Russia’s unprovoked and unjustified invasion of Ukraine and the severe drought in the Horn of Africa region.” Not surprisingly, Biden’s statement came in the wake of what seems like a concerted campaign in mainstream Western media targeting Russia for the crisis (“Russia is weaponising food supplies to ‘blackmail the world’”, a CNBC headline said).

Russian President Vladimir Putin denied the charge, in turn blaming the crisis on the crippling Western sanctions on his country, which have “created conditions that made it much more difficult” to deliver certain products internationally.” He also reportedly confirmed that Russia had not “put any restrictions on the export of fertilisers, or on the export of food products.”

But is the Russia-Ukraine war really behind the present crisis? A closer look indicates otherwise. As a March 2022 World Bank report explained: “Here is a fact which may surprise you: Global stocks of rice, wheat, and maize – the world’s three major staples – remain historically high. For wheat, the commodity most affected by the war, stocks remain well above levels during the 2007-2008 food price crisis. Estimates also suggest that about three-quarters of Russian and Ukrainian wheat exports had already been delivered before the war started.” The report refers to the food security crisis as a “food price crisis,” emphasising that it’s not caused by shortage of food.

Data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO) monthly ‘Cereal Supply and Demand Brief’ confirms this. The FAO’s forecast for global cereal production in 2022 has been raised by 7 million tonnes in July from the previous month and is now pegged at 2,792 million tonnes and is only 0.6 percent short of the output for the same period in 2021. According to the FAO, the shortfall caused by the Russia-Ukraine war has not impacted global wheat stocks much, thanks to higher-than-normal harvests.

An assessment by the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES), too confirms that there is currently no risk of global food supply shortages. The IPES too identifies it as a “food price crisis,” but goes on to identify the causes. Stating that “the failure to reform food systems has allowed the war in Ukraine to spark a third global food price crisis in 15 years,” the report points to “fundamental flaws in global food systems – such as heavy reliance on food imports and excessive commodity speculation – for escalating food insecurity sparked by the Ukraine invasion,” adding that “these flaws were exposed, but not corrected, after previous food price spikes in 2007-8.”

Yet another report, by Navdanya, the organisation founded by environmental activist Vandana Shiva, goes even further: it points to the evidence outlined above and says that the present crisis is the direct outcome of a broken global food system that exists primarily to serve agribusiness giants.”

The report, titled Sowing Hunger, Reaping Profits – A Food Crisis by Design, traces the crisis to excessive financial speculation, increased commodity future pricing and increased volatility in the market, all of it adding up to bigger gains for corporate players, even as it drives up food prices globally. As Shiva puts it, “what the Russian-Ukrainian conflict has once again laid bare is just how fragile globalised food systems are, and how quickly a fluctuation in the market goes on to detrimentally affect the poorest. The current globalised, industrial agri-food system creates hunger by design.”

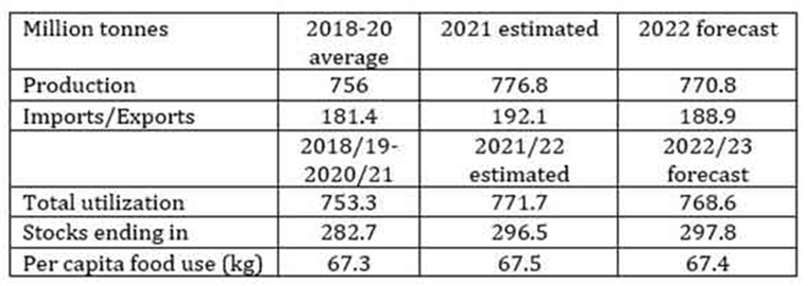

An analysis of global wheat prices by economists CP Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh reinforces this. Examining FAO data and projections from May 2021, much before the Russia-Ukraine war commenced, they find that the estimated global production of wheat in 2022 is likely to be lower than in 2021 by less than 1%, but around 2% higher than the average of 2018-20. Similarly, global trade in wheat is also projected to fall slightly when compared to 2021, but it will still remain higher than in 2018-20.

The two major factors they have identified as driving the crisis are, “profiteering by major grain trading agribusinesses, which have already shown dramatic increases in profitability in January-March 2022 as they have raised their prices without being questioned, as everyone assumes that this is the result of war-driven supply shortages. The other is financial speculation in wheat futures markets, which can drive up prices even in spot markets.”

As a recent Rolling Stone magazine report summed up, “this crisis… is in some sense artificial, given that it is not driven by any actual shortage of food in the world,” adding, “Commodity traders make money off wild price swings, shippers make money off people desperate for grain, fertiliser manufacturers make money off farmers desperate to maximize their yields, and proto-fascist politicians are happy to exploit rising food prices as evidence of the failure of democracy.”

It’s important to note that a country like the UK, where civil society is calling for a food emergency to be declared, is not on the UN’s list of 107 severely affected nations, thus revealing the sheer gravity of the crisis in these nations. Multi-billion-dollar pledges apart, official efforts to tackle the crisis seem to be failing, even in rich nations.

The conclusion is stark. Without concerted efforts by citizens to force governments to act, the accelerating hunger and livelihoods crisis will engulf the majority of humanity, with grave and unforeseen consequences. Beyond that, it calls for a radical transformation of a global agricultural-industrial-financial system designed to reap windfall gains for a handful of big corporations and investors, even as it puts billions at risk.

[Global wheat production. Source: FAO Food Outlook June 2022]

Back to Home Page

Frontier

Vol 55, No. 7, Aug 14 - 20, 2022 |